Teburoro Tito

Teburoro Tito | |

|---|---|

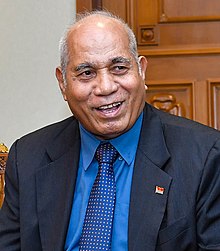

Tito in August 2019 | |

| Permanent Representative of Kiribati to the United Nations | |

| Assumed office 13 September 2017 | |

| President | Taneti Maamau |

| 3rd President of Kiribati | |

| In office 1 October 1994 – 28 March 2003 | |

| Vice President | Tewareka Tentoa Beniamina Tinga |

| Preceded by | Ata Teaotai (acting) |

| Succeeded by | Tion Otang (acting) |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 25 August 1953 (age 70) Tanaeang, Tabiteuea, Gilbert and Ellice Islands (now Kiribati) |

| Political party | Christian Democratic Party (1994–2002) Protect the Maneaba (2002–) |

| Spouse | Keina Tito |

Teburoro Tito (born 25 August 1953) is an I-Kiribati politician and diplomat who served as the third president of Kiribati from 1994 to 2003.

Early life

[edit]Teburoro Tito was born in Tanaeang, a village in Tabiteuea North, on 25 August 1952 or 1953.[1][2][a] In 1971, Tito received a government scholarship to attend the University of the South Pacific in Fiji. He was the president of the students' association in 1976 and 1977. Tito graduated in 1977 with a Bachelor of Science and a Certificate in Education. Afterwards, he stayed at the university until 1979 as the student coordinator.[2][4]

Early political career

[edit]In 1980, Tito returned to Kiribati and became a Scholarship Officer for the Ministry of Education. In 1982, he went on a thirty-day study tour in the US "for future leaders." Tito served as Senior Education Officer from 1983 to 1987. Tito, a keen soccer player, also chaired the Kiribati Football Association from 1980 to 1994.[2]

In March 1987,[5] Tito was elected as member of parliament for the Teinainano Urban Council constituency in South Tarawa. In the presidential election later that year, Tito was one of three final candidates.[2][6] Opposition leader Harry Tong had originally been considered as a candidate, but he stepped aside in favour of Tito. The other two candidates, Ieremia Tabai and Teatao Teannaki, were the incumbent president and vice-president.[7]

Tito built a reputation as "an energetic, highly articulate man" and, as a Catholic candidate, garnered the favour of Catholic voters,[7] who formed much of the opposition to Tabai's government.[8] Both Tabai and Tito limited their campaigning to the islands where they were most popular—Tabai in the south and Tito in the north—forgoing any attempt to garner votes from the other candidate's strongholds.[9] Tito lost to Tabai, but received the highest vote share for any opponent of Tabai's government since independence with 42.7%.[7] It was speculated that Teannaki, an ally of Tabai, split the Catholic vote in a way that made him a spoiler candidate for Tito.[9]

As part of the Christian Democratic Party (MTM), Tito became opposition leader until 1990, when he served as deputy leader until 1994.[2][10] Tito was also a member of the Public Accounts Committee from 1987 to 1990 and the Commonwealth Parliamentary Association (CPA) Executive Committee from 1988 to 1989, attending overseas conferences and meetings.[2]

Presidency

[edit]1994–1998

[edit]In 1994, Tito and three other candidates, all from the MTM, were nominated for the presidential election. There had been claims of misconduct against the outgoing government, and a brief constitutional crisis ensued when acting president Tekiree Tamuera was forcibly removed. Tito won the election in a landslide victory with 51% of the votes.[2][10]

Tito has called attention to the detrimental effects of global warming on Pacific Island nations.[11] He has complained that large countries do not do enough to offset their contributions to climate change, while small countries such as Kiribati suffer the effects. He compared the situation to ants on a leaf being bothered by elephants roughhousing in the pond. "The problem isn't the ants' behavior [but] of how to convince the elephants to be more gentle."[12] Still, Tito is sceptical of scientists and politicians who say that rising sea levels will inevitably submerge Kiribati, citing Genesis 9:11.[13]

The International Date Line used to run through Kiribati. Fulfilling a campaign promise, Tito declared that the Date Line would run along his country's eastern border effective 1 January 1995. This made the Line Islands of Kiribati the first region in the world to see the new day. The decision attracted little attention until other Pacific countries disputed the claim after the millennium celebrations approached.[14][15] Other Pacific nations tried to move the Date Line, temporarily implement daylight saving time, and claim the "first territory", "first land", "first inhabited land" or "first city" to enter 2000.[16]

1998–2002

[edit]The Christian Democratic Party and the main opposition both lost seats in the 1998 parliamentary election. On 27 November, Tito was re-elected with 52% of the vote, while Harry Tong received only 46%.[2]

On 14 April 1999, Tito wrote a letter requesting Kiribati's admission to the United Nations,[17] which was accepted.[18] Tito attended the millennium celebrations on Caroline Island, which the government had renamed Millennium Island. As the easternmost of the Line Islands, Caroline would be the first place in the world to enter 1 January 2000. BBC News' Mike Donkin reported that Tito spoke with emotion as his country found itself at the centre of attention. "Our elders tell us that in our ancient myths and legends these islands were where creation began," Tito said. "This particular moment in history seems to confirm the mythology of our ancestors."[19]

2002–2003

[edit]In February 2003, Tito was re-elected over Taberannang Timeon by 547 votes. A major election issue was the Chinese satellite tracking station on Tarawa. Set up in 1997, it was China's only offshore satellite facility and played a role in the Chinese space program by tracking the first person they sent into space. However, there were concerns about potential military use and allegations that it was used to monitor the US Kwajalein Missile Range.[20][21] When MP Harry Tong asked Tito to release details about China's 15-year lease, Tito refused. He also asked Tito about Chinese ambassador Ma Shuxue acknowledging that the Chinese government had donated $2,850 to a cooperative society linked to Tito.[21] There was another controversy when Tito leased an ATR-72-500 aircraft at the government's expense, losing A$8 million during the first six months.[22] In March, parliament was dissolved after a 40–21 vote of no confidence against the Tito government.[21]

Post-presidency

[edit]In September 2017, Tito resigned from parliament to become the country's Permanent Representative to the United Nations.[23] In 2018, President Taneti Maamau appointed Tito as Ambassador to the United States.

In June 2024, Tito offered Leticia Carvalho a potential high-level staff role at the International Seabed Authority, the body which regulates mining on the seabed, in exchange for ending her bid to become its secretary general. This would leave the candidate Kiribati sponsors, incumbent Michael Lodge, unopposed. Kiribati struck a deal with The Metals Company to secure mining access to Pacific Ocean sectors governed by the Seabed Authority, which would be thwarted if conservation-minded Carvalho was successful. Carvalho refused.[24]

Personal life

[edit]Tito is married to Keina Tito, with whom he has one child.[2] He also has a granddaughter.[1]

Before Tito became president, Lodge was his family lawyer. He represented them when Tito's sister died during childbirth after being improperly sedated.[24]

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "New Permanent Representative of Kiribati Presents Credentials" (Press release). United Nations. 13 September 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i East & Thomas 2003, pp. 274–275.

- ^ Geddes, W. H. (1983) [1975]. Tabiteuea North. ANU Development Studies Centre. ISBN 0-909150-89-3.

- ^ Van Trease 1993, p. 377.

- ^ Van Trease 1993, p. 68.

- ^ Van Trease 1993, pp. 68, 70.

- ^ a b c Van Trease 1993, p. 70.

- ^ Van Trease 1993, p. 63.

- ^ a b Bataua, Batiri T. (1 July 1987). "Kiribati election results". Pacific Islands Monthly. Vol. 58, no. 7. p. 24.

- ^ a b "Freedom in the World 1998 - Kiribati". Freedom in the World. 1998. Retrieved 15 August 2024.

- ^ Warne, Kennedy (November 2015). "Rising Seas Threaten These Pacific Islands but Not Their Culture". National Geographic. Retrieved 15 August 2024.

- ^ Kristof, Nicholas D. (2 March 1997). "In Pacific, Growing Fear of Paradise Engulfed". The New York Times. Retrieved 15 August 2024.

- ^ Reed, Brian (17 November 2010). "Climate Change Debate Within Kiribati". NPR. Retrieved 28 May 2024.

- ^ Kristof, Nicholas D. (23 March 1997). "In Pacific Race to Usher In Millennium, a Date-Line Jog". The New York Times. Section 1, p. 8. Retrieved 15 August 2024.

- ^ Ariel & Berger 2005, p. 149.

- ^ Aimee, Harris (1999). "Millenium: Date Line Politics". Honolulu Magazine (August ed.): 20. Archived from the original on 28 June 2006. Retrieved 21 November 2012.

- ^ "Security Council Refers Application Of Republic Of Kiribati For UN Membership To Committee On Admission Of New Members For Examination" (Press release). United Nations. 4 May 1999. SC/6669. Retrieved 16 August 2024.

- ^ Markisz, Susan (14 September 1999). Kiribati, Nauru and Tonga Admitted to United Nations Membership (Photograph). United Nations Photo Library. Retrieved 16 August 2024.

- ^ Donkin, Mike (24 December 1999). "Voyage to the third millennium". BBC News. Retrieved 16 August 2024.

- ^ Fickling, David (1 December 2003). "Diplomacy for sale". The Guardian. Retrieved 15 August 2024.

- ^ a b c Piano & Puddington 2004, pp. 308–310.

- ^ Pareti, Samisoni (January 1, 2004). "Why Kiribati's Switching Alliance". Pacific Magazine. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007.

- ^ "Tito resigns from Kiribati parliament". Radio New Zealand. 4 September 2017. Retrieved 16 August 2024.

- ^ a b Lipton, Eric (4 July 2024). "Fight Over Seabed Agency Leadership Turns Nasty". The New York Times. Retrieved 16 August 2024.

Bibliography

[edit]- Ariel, Avraham; Berger, Nora Ariel (2005). Plotting the Globe: Stories of Meridians, Parallels, and the International Date Line. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9780313056468.

- East, Roger; Thomas, Richard J. (2003). Profiles of People in Power: The World's Government Leaders. Routledge. ISBN 9781317639404.

- Piano, Aili; Puddington, Arch, eds. (2004). "Kiribati". Freedom in the World 2004: The Annual Survey of Political Rights and Civil Liberties. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 308–310. ISBN 0-7425-3644-0.

- Van Trease, Howard, ed. (1993). Atoll Politics: The Republic of Kiribati. Macmillan Brown Centre for Pacific Studies. ISBN 978-0-9583300-0-8.

- 1953 births

- Living people

- Presidents of Kiribati

- Foreign ministers of Kiribati

- Ambassadors of Kiribati to the United States

- Permanent Representatives of Kiribati to the United Nations

- People from the Gilbert Islands

- Protect the Maneaba politicians

- 20th-century I-Kiribati politicians

- 21st-century I-Kiribati politicians

- Recipients of orders, decorations, and medals of French Polynesia

- 20th-century presidents in Oceania

- Oceanian politician stubs

- I-Kiribati people stubs